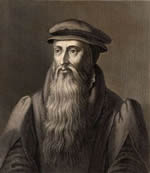

Patrick Hamilton

Patrick Hamilton was the first martyr of the Scottish Reformation – the first person to die for his faith. He was born 1504 into a rich family who were related to the king. At the age of about fourteen he went to university in Paris. While he was there he heard about the teachings of Martin Luther. Luther had been a priest but now he was teaching and writing about the corruption and false teaching of the Roman Catholic Church. Luther was shocking everyone by declaring that men and women could only get to Heaven by putting their faith in Jesus Christ, and not by their good works. He said that people should be allowed to read the Bible for themselves to see if what he was saying was true.

After finishing university in France, Hamilton came home and in 1524 became a Professor at the University of St Andrews. Luther’s books were banned in 1525 but many copies of them were still available, along with the first translation of the Bible from Greek into English by William Tyndale in 1526. Hamilton became convinced that Luther’s teachings were from the Bible and was converted. However St Andrews was the centre of Roman Catholicism in Scotland at this time and his new beliefs attracted the attention of Archbishop James Beaton in 1527. Twenty-three year old Hamilton was not yet ready to take on the Roman Catholic Church, so he fled to Germany.

In Germany, Hamilton wrote a book called Patrick’s Places. The main point of the book was that people can only be saved through faith in Christ and not by good works. At the centre of everything Patrick Hamilton believed and taught was Jesus Christ and what He had done. He became determined to go back to Scotland to preach the good news, even though he knew it would be to risk his life.

Patrick therefore returned home and devoted himself to preaching. His brother and sister both became believers through his preaching and many others followed. Archbishop Beaton quickly became aware of his return however and summoned Patrick to appear before him. His accusers allowed him to preach openly in the university for about a month, hoping that he would it would give them more evidence against him. However instead many important people were converted.

On the 29th of February Hamilton was summoned for trial. He refused to deny his beliefs and was sentenced to be burnt at the stake the same day for being a heretic (accepting false doctrines). His death was slow and painful because the fire kept going out, and it took him six hours to die. His death was a turning point however. Archbishop Beaton was advised that if he had to burn any more heretics, he should do it in deep cellars so that no-one would know, because ‘the reek of Mister Patrick Hamilton has infected as many as it blew upon’. His courage, brilliance and gentleness inspired many. Throughout Scotland, as people heard of his death, they began to ask why it had happened. The teaching of God's Word, instead of dying, spread.

Application

The life of Patrick Hamilton shows us how important it is that we

don’t just accept what we’re taught, but we check that it’s from the

Bible. It also shows us the importance of preaching. It is so important

that Patrick Hamilton was prepared to die rather than stop doing it.

This reminds us how important it is that we, our families and our

friends hear the preaching of God’s word.

George Wishart

George Wishart was born in Scotland in 1513. He was tall, with black hair and a long beard. He went to university in France (Louvain) and then became a priest.. By 1538 he was back in Scotland as a school teacher in Montrose, where he taught his students the New Testament in Greek. When the Bishop of Brechin heard that Wishart was teaching young men to read the Bible in its original language he was furious. Wishart fled to Bristol, where he got in trouble for his preaching, and he spent the next three years in Switzerland and Germany. In 1542 he taught at Cambridge University, where he was well known for his kindness and generosity towards others. He often gave his clothes and bed-sheets to the poor. In 1543, Wishart returned to Scotland where he preached in Montrose, Dundee and the West. In 1545, plague broke out in Dundee and as soon as Wishart heard of it he went back there, preaching to everyone and caring for the sick. He told them how there was a worse disease than the plague - sin - which could only be healed by the Lord Jesus Christ. Cardinal David Beaton, nephew of the Archbishop who had put Patrick Hamilton to death, sent a priest to kill Wishart with a dagger. However Wishart took the dagger off the priest before defending him from the angry crowd. Wishart survived another attack on his life by Beaton before finally being arrested near Edinburgh in 1546. By this time, a man called John Knox was following Wishart round as a bodyguard, carrying a large two-handed sword. However Wishart wouldn't let Knox come with him to his trial and execution. "One is sufficient for one sacrifice", he said. Wishart was taken to St Andrews and kept in prison in the dungeon of the castle. At his trial, he was found guilty of being a heretic because of what he had been preaching, even though he answered all the accusations against him by quoting from the Bible. He was then hanged and burnt at the stake outside the castle. His preaching had helped unite believers across Scotland, and like Patrick Hamilton, his death actually furthered the spread of the gospel.

George Wishart was prepared to die rather than stop believing in the truth, once he had found it in the Bible. His life shows us the importance of preaching. His preaching around Scotland for over two years helped to transform the nation. Preaching is still what we need to change our country today. But as well as preaching to people, Wishart also cared for the physical needs of those who were poor and sick. Like Jesus and the apostles we should care for people's physical needs as well as their spiritual needs. Wishart also knew his Bible so well he could quote from it during his trial and prove that what he had been teaching was from God's Word. How well would we know God's Word if we didn't have it in front of us? |

John Knox

John Knox, the most famous Scottish Reformer, was born near Edinburgh in 1505. He went to his local school and then to university in St Andrews, before becoming a deacon and a priest in the (Roman Catholic) Church.

From 1542, Scotland was governed by Regent Arran as Mary Queen of Scots was still a baby. Arran benefited reform in Scotland in a number of ways. Firstly, he passed a law that allowed people to read the Bible in their own language. He then appointed the Protestant Thomas Guillame to preach around Scotland, and it was through his preaching that John Knox was converted. The biggest influence on Knox’s life however was George Wishart

After Wishart’s death in 1546, Knox taught the sons of a number of Protestants who had captured St Andrews Castle. Some of those in the castle called Knox to become their minister. At this he burst into tears and ran off to his room because of what a responsibility he knew it would be. A few days later however he accepted the call. In the summer of 1547 French warships attacked the castle. Knox was taken prisoner, kept aboard in one of the ships and forced to row it in chains with other galley slaves. After 19 months however he was set free, and went to England where Archbishop Cranmer was working to promote the Reformation, and he was appointed as a preacher [in Berwick]. He attacked the Roman Catholic mass as idolatry because it was ‘invented by the brain of man’ and not commanded by God. In 1551 he was invited to live in London and preach before king Edward VI.

In 1553, the Roman Catholic Mary I became Queen. Knox was now in danger so he left for Europe. He became minister in Frankfurt in Germany and then in Geneva in Switzerland where John Calvin was also a minister. In between he returned to Scotland to get married and preach, and was surprised at how far the teaching of the Reformers was spreading.

In 1559, he came back to Scotland for good. The Scottish people were now ready to end Roman Catholicism once and for all, after the death of Walter Mill. Knox began to preach throughout Scotland, and God saved many people. In the autumn, he became minister at St Andrews. The people in St Andrews had been convinced by Knox’s preaching and had taken all the pictures and images out of the church.

1560 was the key year in the First Scottish Reformation. The Scottish Parliament passed laws getting rid of the mass and the Pope’s power in Scotland. Knox and five other men, all called John, wrote important documents such as the Scots Confession of Faith, which explained what the church believed. In the summer, Knox became minister in Edinburgh. In December, the first General Assembly met in Edinburgh.

From 1567 until he was assassinated three years later, Scotland was ruled by the Protestant Regent Moray. The second Reformation Parliament met in the same year and passed more laws in favour of the Reformation. The years from 1560 onwards saw worship simplified, evangelism, care of the poor and more education, so the ordinary people could read the Bible. Instead of the outward forms of Roman Catholicism, public worship was now based around reading, preaching and singing from God’s word.

Knox continued preaching for the rest of his life and died in 1572. When he was buried, it was said that ‘Here lies a man who in his life never feared the face of man’.

John Knox saw how important it was for the church to do what the Bible said, and not just what they thought was right. He wasn’t afraid to stand up to anyone, even kings and queens, for what he knew was right. His preaching was used by God to transform the whole of Scotland.

On the 23rd of July 1637, in St Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh, Dean Hannay attempted to read from the prayer book for the first time. At this, a woman called Jenny Geddes picked up the stool she was sitting (pictured above) and threw it at his head, shouting “Villain, dost thou say mass at my lug? [in my hearing]”. Then a riot broke out, with more people shouting and throwing stools, before leaving the building.

The next day, the privy council (which governed Scotland) forbade speaking against the government or prayer book on pain of death. However due to the opposition they ordered that the prayer book not be used until king Charles I, in London, had been told about the situation. Many protests and petitions against the prayer book were made to the privy council, condemning it as containing errors and being forced on the church without being the approval of a General Assembly or Parliament.

David Dickson

Protests against the prayer book

David Dickson was born in 1583 and was minister in Irvine before becoming a Professor of theology at Glasgow University. Along with Alexander Henderson, David Dickson led the protests against the Book of Common Prayer in 1637 after the first attempt to read it had been interrupted by Jenny Geddes. They had planned the opposition to the prayer book in the months before it was introduced, and now Dickson helped organise petitions to the privy council against the prayer book. These protests condemned the prayer book as containing errors and being forced on the church without having the approval of a General Assembly or Parliament. The privy council wrote to the king telling him of the opposition to the prayer book from all sorts of people from different parts of the country.

On the 17th of October, the king ordered that all the protesters were to leave Edinburgh within 24 hours. However the nobles, lairds and ministers stayed on to present another protest. They handed in this ‘Supplication’, signed by many of the most important people in Scotland, and then returned home. The Supplication protested not just against the prayer book, but also the Book of Canons and the bishops themselves.

In November, the protesters came back to Edinburgh and set up “The Four Tables” (made up of nobles, lairds, burgesses and ministers) which would meet to represent them. Dickson played an important role in their organisation. The Tables blamed the bishops for the situation rather than the king and in December they wrote another protest which said they rejected the bishops’ authority. However the king still wouldn’t listen to their complaints, and took full responsibility for ordering the bishops to write the Book of Canons and Book of Common Prayer. He declared that any more meetings of the protestors would be seen as treason. Now the Presbyterians knew that their teachings and worship of their church were not just being attacked by the bishops, but by the king himself. Dickson and others realised that something had to be done, and they wrote to their supporters telling them to come to Edinburgh.

David Dickson died in 1662. His last words were:

“I have taken all my good deeds, and all my bad deeds, and cast them in a

heap before the Lord, and fled from both to the Lord Jesus Christ, and

in him I have sweet peace”

Author of the Covenants

Alexander Henderson was minister at Leuchars, near St Andrews, and then in St Giles in Edinburgh. He has been described as ‘easily the most important covenanting minister’ but he had not even been a Christian when he became a minister in 1612! He had to climb in a window to get into his new church building as the people had locked the door. However after going secretly to hear the famous Robert Bruce preaching (on John 10v1) he was converted. After this he became a strong defender of Presbyterianism and led the opposition to the Five Articles of Perth at the General Assembly of 1618.

Henderson wrote one of the three sections of the National Covenant of 1638, was Moderator of the Glasgow Assembly of the same year and ‘in the crucial few years that followed, his leadership cannot be overestimated’. His fellow minister Robert Baillie described him as ‘incomparably the ablest man of us all for all things’. Henderson was also the main author of the Solemn League and Covenant of 1643 and one of the Scottish commissioners to the Westminster Assembly.

He died in Edinburgh in 1646 and was buried in Greyfriars kirkyard. He had been behind almost every important development in the Covenanting movement since 1637. At the General Assembly the following year, Baillie declared that Henderson ‘ought to be accounted by us and posterity, the fairest ornament, after John Knox, of incomparable memory, that ever the church of Scotland did enjoy’

Johnston of Wariston was a successful lawyer whose clients included important people in the government, such as the chancellor and the lord treasurer. He also kept a diary which tells us a lot of extra information about events which took place during the 1630s.

He has been described as ‘unusually devout, even by seventeenth-century standards’ and he often prayed for up to three hours at a time. He once prayed from six in the morning till eight at night because he lost track of the time. He wrote in his diary that the success or failure of the Covenanters would depend on their own personal relationships with God.

In 1637, Wariston was involved in the opposition to the Book of Common Prayer and in 1638, at the age of 27, he was given the responsibility of writing the legal section of the National Covenant. This contained a list of all the Acts of Parliament against Roman Catholicism. Wariston’s legal skills, as Charles I’s legal advisor's had to admit, ensured the covenant didn’t break the law of the land. At the Glasgow Assembly of 1638 Wariston was appointed clerk and produced the minutes of all the previous General Assemblies since 1560 – using them to argue that episcopacy had always been condemned in the reformed Church of Scotland.

Wariston continued writing for the Covenanting cause, and wrote their official protestations to the king’s proclamations against them. During the Bishops' Wars he accompanied the army as a legal advisor, and he was involved in peace negotiations with the king. In 1643, he was also appointed as one of the Scottish Commissioners to the Westminster Assembly.

In the following years Wariston was very involved in the government of Scotland and in 1649 he was given the responsibility of putting the Act of Classes into practice.

When Charles II was restored as king in 1660, Wariston was charged with high treason and fled to Germany and then France, but he was eventually caught, arrested and hanged in Edinburgh in 1663.

Andrew Melville

Andrew Melville, after finishing his classical studies, went abroad, and taught for some time, both at Poitiers in France, and at Geneva. He returned to Scotland in July 1574, after having been absent from his native country nearly ten years. Upon his return, the learned Beza, in a letter to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, said, “The greatest token of affection the kirk of Geneva could show to Scotland was, that they had suffered themselves to be spoiled of Mr Andrew Melville.”

Soon after his return, the General Assembly appointed him to be the Principal of the College of Glasgow, where he continued for some years. In the year 1576, the Earl of Morton being then Regent, and thinking to bring Andrew Melville into his party, who were endeavouring to introduce Episcopacy, he offered him the parsonage of Govan, a benefice of twenty-four chalders of grain yearly, besides what he enjoyed as Principal, providing he would not insist against the establishment of bishops; but Melville rejected his offer with scorn.

He was afterwards translated to St Andrews, where he served in the same station as he had done at Glasgow; and was likewise a minister of that city. Here he taught the divinity class, and, as a minister, continued to witness against the encroachments then making upon the rights of the Church of Christ.

When the General Assembly sat down at Edinburgh in 1582, Andrew Melville inveighed against the absolute authority which was making its way into the Church: whereby, he said, they intended to pull the crown from Christ’s head, and wrest the sceptre out of His hand. When several articles, of the same tenor with his speech, were presented by the commission of the Assembly to King James VI. And Council, craving redress, the Earl of Arran cried out, “Is there any here that dare subscribe these articles.” Melville went forward and said, “We dare, and will render our lives in the cause;” and then took up the pen and subscribed. We do not find that any disagreeable consequences ensued at this time.

But in the beginning of February 1584, he was summoned to appear before the Secret Council, on the 11th of that month, to answer for some things said by him in a sermon on a fast-day, from Dan 4. At his first compearance, he made a verbal defence; but being again called, he gave in a declaration, with a declinature, importing that he had said nothing, either in that or any other sermon, tending to dishonour King James VI., but had regularly prayed for the preservation and prosperity of his Majesty; that, as by acts of Parliament and laws of the Church, he should be tried for his doctrine by the Church, he therefore protested for, and craved, a trial by them, and particularly in the place where the offence was alleged to have been committed; and that as there were special laws in favour of St Andrews to the above import, he particularly claimed the privilege of them. He further protested, that what he had said was warranted by the word of God; that he appealed to the congregation who heard the sermon; that he craved to know his accusers; that, if the calumny was found to be false, the informers might be punished; that the rank and character of the informer might be considered, etc., after which he gave an account of the sermon in question; alleging that his meaning had been misunderstood, and his words perverted.

When he had closed his defence, the King, and the Earl of Arran, who was then Chancellor, raged exceedingly against him. Melville remained undisquieted, and replied, “You are too bold, in a constituted Christian kirk, to pass by the pastors, and take upon you to judge the doctrine, and control the messengers of a Greater than any present. That you may see your rashness, in taking upon you that which you neither ought nor can do” (taking out a small Hebrew Bible, and laying it down before them), “there are,” said he, “my instructions and warrant, - see if any of you can control me, that I have passed my injunctions.” The Chancellor opening the book, put it into the King’s hand, saying, “Sire, he scorneth your Majesty and the Council.” “Nay,” said Andrew Melville, “I scorn not, but I am in good earnest.”

He was, in the time of this debate, frequently removed, and instantly recalled, that he might not have time to consult with his friends. They proceeded against him, and admitted his avowed enemies to prove the accusation; and though the whole train of evidence which was led, proved little or nothing against him, yet they resolved to involve him in troubles, because he had declined their authority, as the competent judges of doctrine, and therefore remitted him to ward in the Castle of Edinburgh, during the King’s will. Being informed, that if he entered into ward, he would not be released, unless it should be to bring him to the scaffold, and that the decree of the Council being altered, Blackness was appointed for his prison, which was kept by some dependants of the Earl of Arran, he resolved to get out of the country. A macer gave him a charge to enter Blackness in twenty-four hours; and, in the meanwhile, some of Arran’s horsemen were attending at the West Port to convoy him thither; but, by the time he should have entered Blackness, he had reached Berwick. Messrs Lawson and Balcanquhal gave him the good character he deserved, and prayed earnestly for him in public, in Edinburgh; which both moved the people and galled the Court exceedingly.

After the storm had abated, he returned to St Andrews in 1586, when the Synod of Fife had excommunicated Patrick Adamson, pretended Archbishop of St Andrews, on account of some immoralities. Adamson having drawn up the form of an excommunication against Andrew Melville and James, his brother, sent out a boy with some of his own creatures to the kirk to read it; but the people paying no regard to it, the Archbishop, though both suspended and excommunicated, would himself go to the pulpit to preach; whereupon some gentlemen, and others in town, convened in the new college, to hear Andrew Melville. The Archbishop being informed that they were assembled on purpose to put him out of the pulpit and hang him, for fear of this called his friends together, and betook himself to the steeple; but at the entreaty of the magistrates and others, he retired home.

This difference with the Archbishop brought the Melvilles again before the King and Council, who, pretending that there was no other method to end that quarrel, ordained Mr Andrew to be confined to Angus and the Mearns, under pretext that he would be useful in that country in reclaiming Papists. Because of his sickly condition, Mr James was sent back to the new college; and the University sending the Dean of Faculty and the masters with a supplication to the King in Mr Andrew’s behalf, he was suffered to return, but was not restored to his place and office until the month of August following.

The next winter, he laboured to give the students in divinity under his care a thorough knowledge of the discipline and government of the Church; which was attended with considerable success. The specious arguments of Episcopacy vanished, and the serious part, both of the town and University, repaired to the college to hear him and Robert Bruce, who began preaching about this time.

After this he was chosen moderator in some subsequent Assemblies of the Church; in which several acts were made in favour of religion, as maintained at that period.

When the King brought home his Queen from Denmark in 1590, Andrew Melville made an excellent oration upon the occasion in Latin, which so pleased the King, that he publicly declared, he had therein both honoured him and his country, and that he should never be forgotten. Yet such was the instability of this prince, that, in a little after this, because Melville opposed his arbitrary measures in grasping after an absolute authority over the church, he conceived a daily hatred against him ever after, as will appear from the sequel.

When Andrew Melville went with some other ministers to the Convention of Estates at Falkland in 1596 (wherein they intended to bring home the excommunicated lords who were then in exile), though he had a commission from last Assembly to watch against every imminent danger that might threaten the Church, yet, whenever he appeared at the head of the ministers, the King asked him, who sent for him there? to which he resolutely answered,

“Sire, I have a call to come from Christ and His Church, who have a special concern in what you are doing here, and in direct opposition to whom ye are all here assembled; but, be ye assured, that no counsel taken against Him shall prosper; and I charge you, Sire, in His name, that you and your Estates here convened favour not God’s enemies, whom He hateth.”

After he had said this, turning himself to the rest of the members, he told them that they were assembled with a traitorous design against Christ, His Church, and their native country. In the midst of this speech, he was commanded by the King to withdraw.

The Commission of the General Assembly was now sitting, and understanding how matters were going on at the Convention, they sent some of their members, among whom Andrew Melville was one, to expostulate with the King. When they came, he received them in his closet. James Melville, being first in the commission, told the King his errand; upon which he appeared angry, and charged them with sedition. Mr James, being a man of cool passion and genteel behaviour, began to answer the King with great reverence and respect; but Mr Andrew, interrupting him, said, “This is not a time to flatter, but to speak plainly, for our commission is from the living God, to whom the King is subject;” and then, approaching the king; said

“Sire, we will always humbly reverence your Majesty in public, but having opportunity of being with your Majesty in private, we must discharge our duty, or else be enemies to Christ. And now, Sire, I must tell you, that there are two kings and two kingdoms in Scotland: there is King James, the head of the Commonwealth, and there is Christ Jesus, the Head of the Church, whose subject King James VI. is, and of whose kingdom he is not a head, nor a lord, but a member; and they whom Christ hath called, and commanded to watch over His Church, and govern His spiritual kingdom, have sufficient authority and power from Him so to do, which no Christian king nor prince should control or discharge, but assist and support, otherwise they are not faithful subjects to Christ. And, Sire, when you were in your swaddling clothes, Christ reigned freely in this land in spite of all His enemies; His officers and ministers were convened for ruling His Church, which was ever for your welfare. Will you now challenge Christ’s servants, your best and most faithful subjects, for convening together, and for the care they have of their duty to Christ and you? The wisdom of your counsel is, that you may be served with all sorts of men, that you may come to your purpose, and because the ministers and Protestants of Scotland are strong, they must be weakened and brought low, by stirring up a party against them. But, Sire, this is not the wisdom of God, and His curse must light upon it; whereas, in cleaving to God, His servants shall be your true friends, and He shall compel the rest to serve you.”

There is little difficulty to conjecture how this discourse was relished by the King. However, he kept his temper, and promised fair things to them for the present; but it was the word of him whose standard maxim was, Qui nescit dissimulare, nescit regnare, “He who knows not how to dissemble, knows not how to reign.” In this sentiment, unworthy of the meanest among men, he gloried, and made it his constant rule of conduct; for in the Assembly at Dundee in 1598, Andrew Melville being there, he discharged him from the Assembly, and would not suffer business to go on till he was removed.

There are other instances of the magnanimity of this faithful witness of Christ, which are worthy of notice. In the year 1606, he, and seven of his brethren, who stood most in the way of having Prelacy advanced in Scotland, were called up to England, under pretence of having a hearing granted them by the King (who had now succeeded to that throne), with respect to religion; but rather to be kept out of the way, as the event afterwards proved, until Episcopacy should be better established in Scotland. Soon after their arrival they were examined by the King and Council, at Hampton Court, on the 20th of September, concerning the lawfulness of the late Assembly at Aberdeen. The King, in particular, asked Andrew Melville whether a few clergy, meeting without moderator or clerk, could make an Assembly? He replied, there was no number limited by law; that fewness of number could be no argument against the legality of the court; especially when the promise was in God’s word given to two or three convened in the name of Christ; and that the meeting was ordinarily established by his Majesty’s laws. The rest of the ministers delivered themselves to the same purpose; after which Andrew Melville, with his usual freedom of speech, supported the conduct of his brethren at Aberdeen, recounting the wrongs done them at Linlithgow, whereof he was a witness himself. He blamed the King’s Advocate, Sir Thomas Hamilton, who was then present, for favouring Popery, and maltreating the ministers, so that the Accuser of the brethren could not have done more against the saints of God than had been done; that prelatists were encouraged, though some of them were promoting the interests of Popery with all their might, and the faithful servants of Christ were shut up in prison. And, addressing the Advocate personally, he added, “Still you think all this is not enough, but you continue to persecute the brethren with the same spirit you did in Scotland.” After some conversation betwixt the King and the Archbishop of Canterbury, they were dismissed, with the applause of many present for their bold and steady defence of the cause of God and truth; for they had been much misrepresented to the English.

They had scarcely retired from before the King, until they received a charge not to return to Scotland, nor come near the King’s, Queen’s, or Prince’s Court, without special license, and being called for. A few days after, they were again called to Court, and examined before a select number of the Scots nobility; where, after Mr James Melville’s examination, Mr Andrew being called, told them plainly, “That they knew not what they were doing; they had degenerated from the ancient nobility of Scotland, who were wont to hazard their lives and lands for the freedom of their country, and the Gospel which they were betraying and overturning.” But night drawing on, they were dismissed.

Another instance of his resolution is this: He was called before the

Council for having made a Latin epigram upon seeing the King and Queen

making an offering at the altar, whereon were two books, two basins, and

two candlesticks, with two unlighted candles, it being a day kept in

honour of St Michael.

The epigram is as follows:

The following is an old and literal translation:

When he compeared, he avowed the verses, and said he was much moved with indignation at such vanity and superstition in a Christian church, under a Christian king, born and brought up under the pure light of the Gospel, and especially before idolaters, to confirm them in idolatry, and grieve the hearts of true professors. The Archbishop of Canterbury began to speak, but Andrew Melville charged him with a breach of the Lord’s-day, with imprisoning, silencing, and bearing down of faithful ministers, and with upholding Antichristian hierarchy and Popish ceremonies; shaking the white sleeve of his rochet, he called them Romish rags, told him that he was an avowed enemy to all the Reformed Churches in Europe, and therefore he would profess himself an enemy to him in all such proceedings, to the effusion of the last drop of his blood; and said, he was grieved to the heart to see such a man have the King’s ear, and sit so high in that honourable Council. He also charged Bishop Barlow with having stated, after the conference at Hampton Court, that the King had said he was in the Church of Scotland, but not of it; and wondered that he was suffered to go unpunished, for making the King of no religion. He refuted the sermons which Barlow had preached before the King, and was at last removed; and order was given to Dr Overwall, Dean of St Paul’s, to receive him into his house, there to remain, with injunctions not to let any have access to him, till his Majesty’s pleasure was signified. Next year he was ordered from the Dean’s house to the Bishop of Winchester’s, where, being not so strictly guarded, he sometimes kept company with his brethren; but was at last committed to the Tower of London, where he remained for the space of four years.

While Andrew Melville was in the Tower, a gentleman of his acquaintance got access to him, and found him very pensive and melancholy concerning the prevailing defections among many of the ministers of Scotland; having lately got account of the proceedings at the General Assembly held at Glasgow in 1610, where the Earl of Dunbar had an active hand in corrupting many with money. The gentleman desired to know what word he had to send to his native country, but got no answer at first; but upon a second inquiry, he said, “I have no word to send, but am heavily grieved that the glorious government of the Church of Scotland should be so defaced, and a Popish tyrannical one set up; and thou, Manderston (for out of that family Lord Dunbar had sprung), hadst thou no other thing to do, but to carry such commissions down to Scotland, whereby the poor Church is wrecked? The Lord shall be avenged on thee; thou shalt never have that grace to set thy foot in that kingdom again!” These last words impressed the gentleman to such a degree, that he desired some who attended the Court to get their business, which was managing through Dunbar’s interest, expedited without delay, being persuaded that the word of that servant of Christ should not fall to the ground; which was the case, for the Earl died at Whitehall a short time after, while he was building an elegant house at Berwick, and making grand preparations for his daughter’s marriage with Lord Walden.

In 1611, after four years’ confinement, Andrew Melville was, by the interest of the Duke de Bouillon, released, on condition that he would go with him to the University of Sedan; where he continued enjoying that calm repose denied him in his own country, but maintaining the usual constancy and faithfulness in the service of Christ, which he had done through the whole of his life.

The reader will readily observe, that a high degree of fortitude and boldness appeared in all his actions; where the honour of his Lord and Master was concerned, the fear of man made no part of his character. He is by Spottiswoode styled the principal agent, or Apostle of the Presbyterians in Scotland. He did, indeed, assert the rights of Presbytery to the utmost of his power against diocesan Episcopacy. He possessed great presence of mind, and was superior to all the arts of flattery that were sometimes tried with him. Being once blamed as being too fiery in his temper, he replied, “If you see my fire go downward, set your foot upon it; but if it goes upward, let it go to its own place.” He died at Sedan, in France, in the year 1622, at the advanced age of 77 years.